Read: 2 Samuel 12:13-31

David said to Nathan, “I have sinned against the LORD.” Nathan said to David, “Now the LORD has put away your sin; you shall not die. Nevertheless, because by this deed you have utterly scorned the LORD, the child that is born to you shall die” (2 Samuel 12:13-14, NRSV).

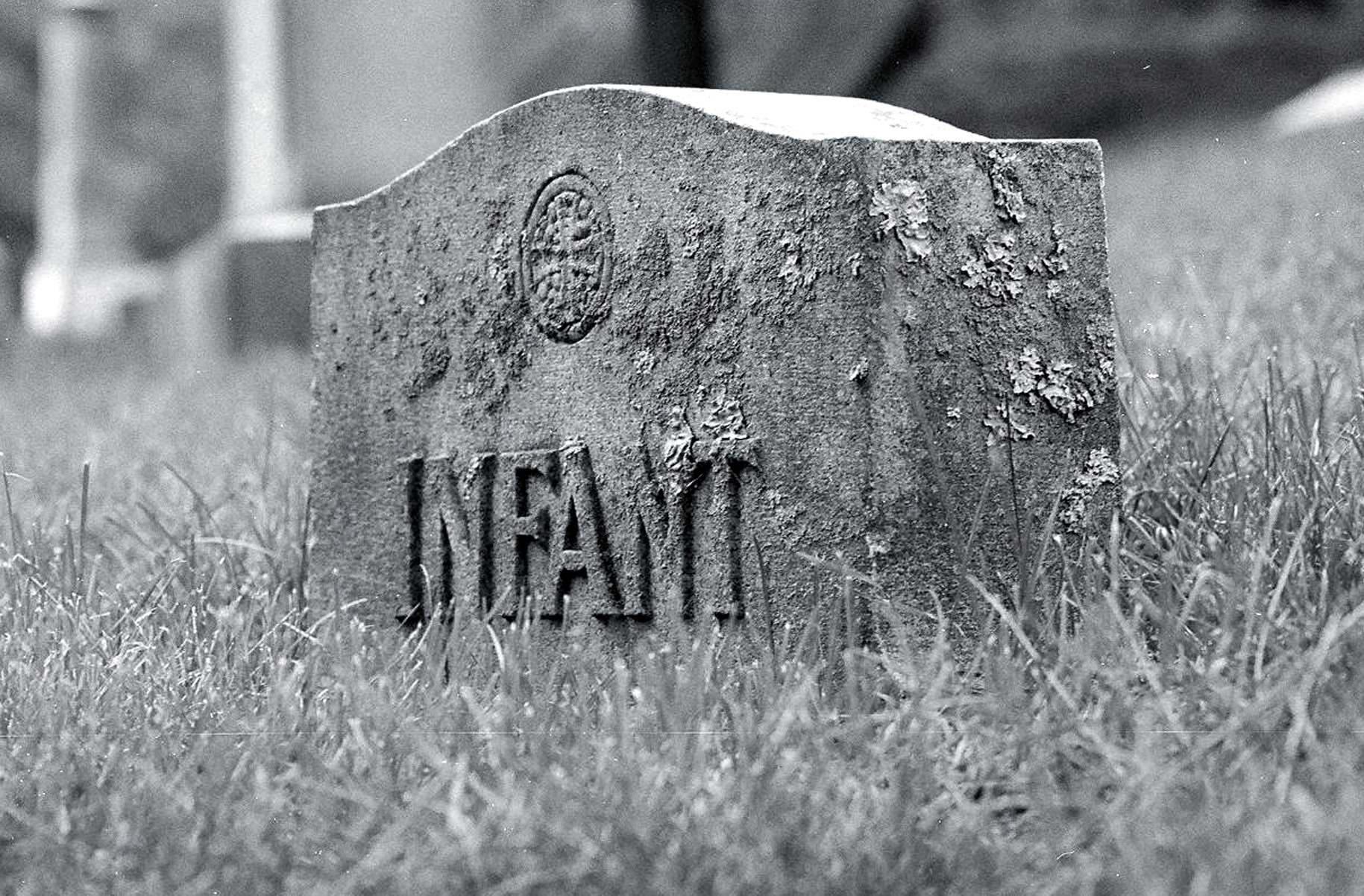

If only we could write off the death of this newborn as collateral damage. In fact, it’s even worse.

Let’s recap. David has admitted his guilt, both for taking another man’s wife (Bathsheba) and for murdering the man (Uriah) in an attempted cover-up. So, points for coming clean—albeit with a lot of help from the prophet Nathan (see vv. 1-12).

David has been indicted. He has pled guilty. Now we’re ready to move on to the sentencing stage of the trial.

Nathan as prophet (a.k.a. prosecuting attorney) now speaks for God (a.k.a. the judge). In view of the defendant’s confession of sin, the sentence has been reduced. Instead of the death penalty for David, the child that is about to be born will die.

Wait! No! That can’t be right! The courtroom—filled with readers from a couple of millennia later—erupts with angry shouts of protest. This isn’t fair! What kind of a God does THAT?

Collateral damage is defined as “any death, injury, or other damage inflicted that is an incidental result of an activity.” It would be bad enough if this innocent baby’s death could be described as collateral damage. But in fact, it’s much worse than that. This baby’s death is not “incidental.” It is described as being willed by God—pronounced as part of David’s punishment. When we read the rest of the chapter, we can see that David does indeed suffer over the illness and eventual death of the child. But what about the baby? What kind of a God punishes a child for the sins of its parent?

Suddenly we find ourselves in deep theological doo-doo. I’m not going to defend God here, because even with a Ph.D. in Old Testament, this is beyond my paygrade. What I will say is that the biblical storyteller is writing from a much less individualistic culture. In this kind of a culture passages like Exodus 34: 6-7 seemed less shocking: “The LORD passed before [Moses] and proclaimed, ‘The LORD, the LORD, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, keeping steadfast love for the thousandth generation, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin, yet by no means clearing the guilty, but visiting the iniquity of the parents upon the children and the children’s children to the third and fourth generation.’”

You can say all you want about the multi-generational punishment “only” being for three or four generations. This still doesn’t sit well with those of us in the 21st century gallery. If it helps, there is evidence that attitudes begin changing about such things even in the Old Testament. Ezekiel 18: 20 proclaims as good news the fact that “The person who sins shall die. A child shall not suffer for the iniquity of a parent.” And the whole book of Job reads like a protest piece against people who attempt to try to explain sin and suffering by using tidy little equations about crime and punishment.

But still. Here we are trying to get our heads around the “sentence” in 2 Samuel 12.

Years ago, when I was in college, I remember trying to come to terms with my young nephew’s suffering. At the tender age of six months, he had been diagnosed with a rare and usually fatal kidney disease. I asked my friends to pray for him. One of them said she would, but she would also pray that God would forgive his sins. “He’s six months old,” I protested. “I don’t think this is about his sins.” “Well then,” she replied. “It must be about something his parents did.”

Needless to say: we did not remain friends. And I suppose I’ve been on a crusade against that kind of theological malpractice ever since. I don’t believe that limited human beings have any business making pronouncements about who is to blame regarding suffering and sin.

What I will say about this troubling passage is that it does testify to the way sin has a way of wreaking havoc all around. In her novel, Adam Bede, George Eliot put it this way: “Consequences are unpitying. Our deeds carry their terrible consequences…consequences that are hardly ever confined to ourselves.”

In the coming chapters, David will learn this lesson over and over again.

Ponder: Have you ever heard the proverb, “The parents have eaten sour grapes and the children’s teeth are set on edge” (see Jer. 31:29-30)? In what ways is that true for you? Not true? How does what we know about generational trauma and family systems relate to this?

Pray: Gracious God, have mercy on those who blame themselves for things that are not their fault. Have mercy on those who think they know more about You than they do.