Read: Romans 5:1-11

But God proves his love for us in that while we still were sinners Christ died for us. Much more surely then, now that we have been justified by his blood, will we be saved through him from the wrath of God (Romans 5:8-9, NRSV).

Sing (or don’t): “In Christ Alone” by Keith Getty & Stuart Townend

It’s a bit like watching an expert gymnast on a balance beam. First, she leaps effortlessly onto the beam. (We know, of course, that this kind of mount is far from effortless, and if it goes wrong, can doom the routine almost before it begins.) Then there is a death and gravity-defying series of flips and twirls. The crowd responds with smatterings of applause, not wanting to distract the athlete, but unable to hold back their admiration. Suddenly, however, their approbation turns to alarm. The gymnast starts to wobble. The crowd gasps as she fights to stay on the beam.

This scenario may seem like a strange way to introduce a hymn text, but in my opinion, there are parallels.

“In Christ Alone” is a profoundly beautiful text by Keith Getty and Stuart Townend that largely deserves every inch of its popularity. It starts out with all the expertise and confidence of our gymnast:

In Christ alone, my hope is found

He is my light, my strength, my song

This Cornerstone, this solid ground

Firm through the fiercest drought and storm

What heights of love, what depths of peace

When fears are stilled, when strivings cease

My Comforter, my All in All

Here in the love of Christ I stand

Incarnational spins and twirls ensue at the beginning of the second verse:

In Christ alone, who took on flesh

Fullness of God in helpless babe

This gift of love and righteousness

Scorned by the ones He came to save

But then comes the wobble:

‘Til on that cross as Jesus died

The wrath of God was satisfied

For every sin on Him was laid

Here in the death of Christ I live, I live

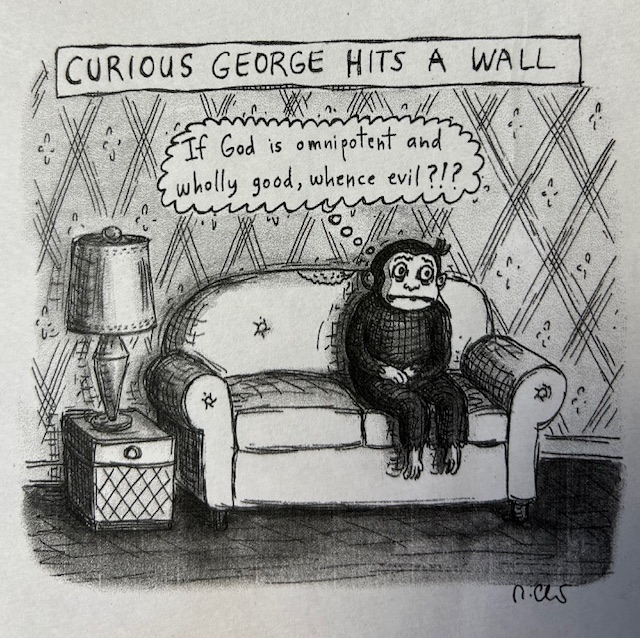

Many of the people in the audience are still applauding, but a few of us are cringing. (There are always a few hard-to-please theologians in every crowd.) “Really?” we’re thinking. “Is Jesus’ death on the cross about satisfying the wrath of God?”

This four-line wobble in the middle of an otherwise wonderful hymn has bothered me ever since I started singing it, so I finally decided to “phone a friend” who knows more about such things than I do. In fact, I contacted two of them. Here’s what they said.

Leanne Van Dyk suggests amending the line to read: “…the love of God was satisfied.” She writes, “The hymn line as is indicates a penal substitutionary view of the atonement which, though certainly present in the tradition, is not the only atonement understanding and, I would say, not the best.” She concludes that “it is probably too much to declare it heretical, but it’s close….”

Suzanne McDonald agrees, saying that the line is “not quite heretical, but without qualification/clarification, it’s definitely deeply misleading, and if that’s all people have by way of ‘atonement theology,’ potentially quite dangerously so.”

If you’ve ever met Suzanne, you’ll be able to hear her voice in the following which I will quote in full which I think is vintage Suzanne McDonald:

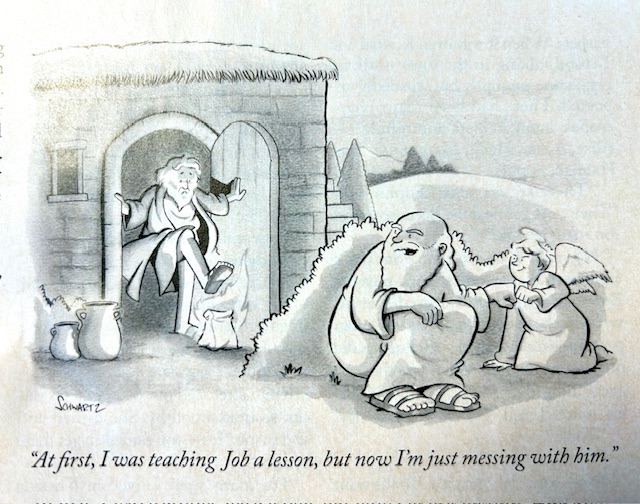

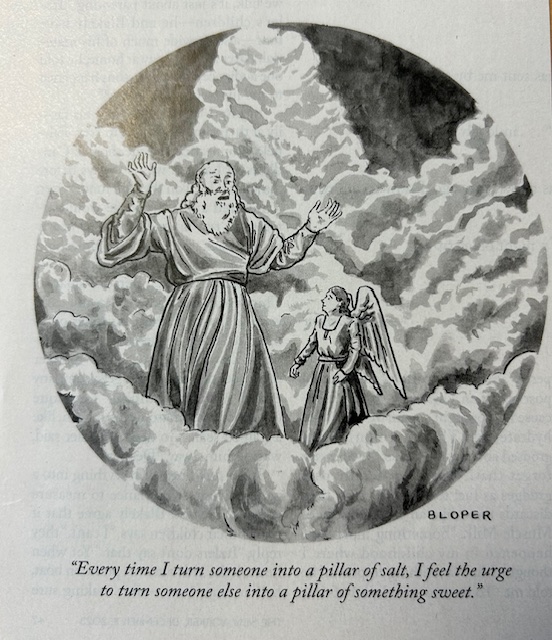

I sometimes call this ‘pub tab’ theology with my students—as in, it makes it sound like sin is the equivalent of running up a tab at the pub. Any suggestion that God’s hands are tied so that he can’t forgive us until he has been ‘paid’ the exact amount/until someone has undergone the precise amount of punishment he requires for all the sin that has ever been or will ever be committed is…unscriptural nonsense. That is just not how either Israel’s sacrificial system or its telos in the cross are presented in scripture. And these verses also walk right up to the line of the sub-Trinitarian ‘cosmic child abuse’ stuff, as if ‘God’ the Father has to be reluctantly persuaded to sort of like us by wrathfully beating up on nice loving Jesus. Blech.

Tempting as it is to conclude with the word, “blech,” I’m going to include the rest of the quote because it does such a good job of keeping us from wobbling off the theological balance beam.

For me, I don’t have a problem with the idea that what happens on the cross is on our behalf and in our place, and that Christ takes upon himself all the consequences of sin that we could never bear for ourselves. The New Testament witness means, I think, we absolutely have to say something like that. But the theological construct that is the ‘penal substitutionary atonement theory’ is mostly an appalling mess. I mean, Romans 5:1-11 for a start!!!!! The cross is the ultimate expression of the undivided love of the whole Triune God for sinners. It does indeed save us from the wrath of God against sin, but not because God has received pub-tab ‘satisfaction’ or has dished out precisely the right amount of retributive punishment to ‘satisfy’ his wrath or justice or whatever. It is because God gives himself out of love in the person of the Son to do everything it takes to reconcile us to himself.

In God’s relationship with Israel, God is always the one who takes the initiative, providing his people both with the means to acknowledge that they have messed up, and what is needed to bring them back into right relationship with himself. So, it’s totally consistent with who God is that all of that should culminate, not in a pub tab, and not in a nasty Father beating up on a nice Son, but in God giving himself for us in reconciling love.

McDonald concludes by affirming Van Dyk’s friendly amendment which would change the text to: “the love of God was satisfied.” I’m not sure the suggestion will be well-received by the hymn’s authors, however. They rejected a similar suggestion from the Presbyterian Committee on Congregational Song, which wanted to change it to “the love of God was magnified.” Some congregations also modify the line (without permission) to read, “the arms of God were open wide.”

What all these suggestions suggest is that a lot of people in the Christian community have noticed the dangerous “wobble” in the middle of this otherwise exquisite hymn. It’s too bad the authors won’t welcome the community’s attempt to help the text regain its balance.

Ponder: Which theory of the Atonement have you been working with? Is it time to make a change?

Pray: Thank you for opening your arms wide to us through the cross, loving God.